Year 2: Neurolocalization Poster

Description

During the Module 8 Continual Assessment Task (CAT), I had a personal matter come up, requiring me to take an unexpected week of leave. This left me to independently complete the task of interpreting clinical and video-based information to achieve accurate neuro-localization for an acute hindlimb paralysis case in a five-year-old Border Collie. The assignment required creating a comprehensive academic poster detailing clinical findings, rationale for neurolocalisation, and appropriate diagnostic and management plans. Given the clinical nature of the task, it necessitated integrating extensive neuroanatomical and physiological principles covered during Module 8.

Critical Reflection

During the Module 8 Continual Assessment Task (CAT), I had a personal matter come up, requiring me to take an unexpected week of leave. This left me to independently complete the task of interpreting clinical and video-based information to achieve accurate neuro-localization for an acute hindlimb paralysis case in a five-year-old Border Collie. The assignment required creating a comprehensive academic poster detailing clinical findings, rationale for neurolocalisation, and appropriate diagnostic and management plans. Given the clinical nature of the task, it necessitated integrating extensive neuroanatomical and physiological principles covered during Module 8.

Initially, the neurology content presented in the module was largely new to me, encompassing extensive information on spinal cord anatomy, neurological pathways, and conditions like intervertebral disc disease (IVDD). Despite the complexity, my enjoyment of the material mitigated feelings of overwhelm, and I approached the task with genuine enthusiasm and curiosity.

Shortly into the task period, a significant personal matter arose, requiring me to take an unexpected week of leave. This development was initially concerning, particularly regarding the completion of the task and my ability to maintain progress. Fortunately, my professor was extremely understanding and supportive, especially since he was also away on family leave during this period. His flexibility and accommodation significantly reduced my anxiety, enabling me to confidently manage the situation independently.

Completing the CAT without peer collaboration posed unique challenges. The primary difficulty was ensuring that my clinical reasoning and diagnostic approach were accurate, as I lacked immediate peer discussion or feedback. To navigate this, I carefully structured my workflow into small, manageable segments and established a detailed day-by-day schedule, setting a clear timeline. I aimed to complete my task with a 20% margin of safety, allowing ample time for review and revision. Throughout this process, I extensively utilized resources such as online veterinary databases, reputable veterinary literature, lecture materials, and evidence-based guidelines, which proved invaluable for verifying my interpretations and decisions.

Upon receiving feedback, it became evident that certain aspects of my neurolocalisation and clinical reasoning required refinement. Initially, I overlooked the clinical significance of withdrawal reflexes and their role in refining lesion localization. Feedback highlighted this gap, clarifying that comprehensive assessment of spinal reflexes could have conclusively localized the lesion to the L4–S3 spinal cord segments rather than suggesting a multifocal lesion. Additionally, I learned that the absence of deep pain sensation reflected lesion severity rather than aiding lesion localization directly. The feedback also brought my attention to fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE), a differential diagnosis I had not considered. Recognizing the classic pattern highlighted in the feedback— 'dog performing exercise and suddenly yelps and present neurological deficits' —was a key learning point in clinical pattern recognition for acute spinal cord diseases.

Furthermore, feedback clarified misconceptions regarding the utility and prioritization of diagnostic imaging options. Initially, I suggested radiography (X-rays) as a potential diagnostic step. The feedback emphasized that while X-rays have limited value for definitively diagnosing soft tissue lesions like IVDD or FCE, they might still be considered in some acute spinal cases as an initial screening tool, particularly if trauma or bony lesions are suspected differentials, before proceeding to advanced imaging like MRI which is superior for visualizing the spinal cord itself. This reinforced the importance of understanding the specific indications and limitations of each imaging modality to guide cost-effective and diagnostically valuable workups. The critique also addressed the sequencing of clinical decision-making and communication, specifically regarding the premature discussion of euthanasia before surgical intervention. Recognizing the prognostic value of timely surgical management, particularly in cases with absent deep pain response, reshaped my perspective on client communication and clinical decision-making.

This CAT experience significantly enhanced my clinical reasoning skills, establishing a critical thinking pathway that will guide future assessments and case management. The constructive feedback illuminated areas needing improvement, reinforcing the necessity of meticulous clinical evaluations, accurate interpretation of neurological examinations, and careful selection of diagnostic strategies. This exercise underscored the importance of clear, evidence-based client communication regarding prognosis and treatment options, which is essential for responsible veterinary practice.

Moving forward, I plan to deepen my understanding and proficiency in neurological examinations, particularly spinal reflex pathways and differential diagnoses of acute spinal cord disorders. To achieve this, I intend to engage in additional focused reading, clinical placement opportunities, and consistent application of spaced repetition techniques. This proactive approach to ongoing learning and reflection will undoubtedly enhance my clinical competence, bolster confidence, and foster continued professional development in veterinary neurology.

(736 words)Outcome Annotations

This assessment contributed to my development in the following Foundation Phase Outcomes:

Annotations

Clinical Assessment

I have practiced interpreting neurological signs and applying knowledge of neuroanatomy to perform systematic neurolocalization. I have developed a logical approach to differential diagnosis based on accurately localizing lesions from clinical presentations, as demonstrated in the poster analysis.

Investigation

I have developed skills in selecting appropriate diagnostic modalities for neurological cases like FCE or IVDE. I have considered the strengths, limitations, cost-effectiveness, and logical sequence of tests (e.g., MRI vs. X-ray), justifying choices based on clinical signs and differentials.

Diseases of Body Systems

I have applied knowledge of neurological diseases affecting canine spinal cord segments (L4-S3), peripheral nerves, and neuromuscular junctions. I have used this understanding to develop comprehensive differential diagnoses for acute hindlimb paralysis, incorporating conditions like IVDE and FCE.

Veterinary Economics

I have considered cost-effective diagnostics, recognizing the financial burden of ineffective tests like radiographs for non-traumatic spinal lesions. I have also developed understanding of the economic implications of treatment choices (e.g., surgery timing, physiotherapy) on client finances and clinical outcomes.

Supporting Materials & References

Neurolocalization Poster

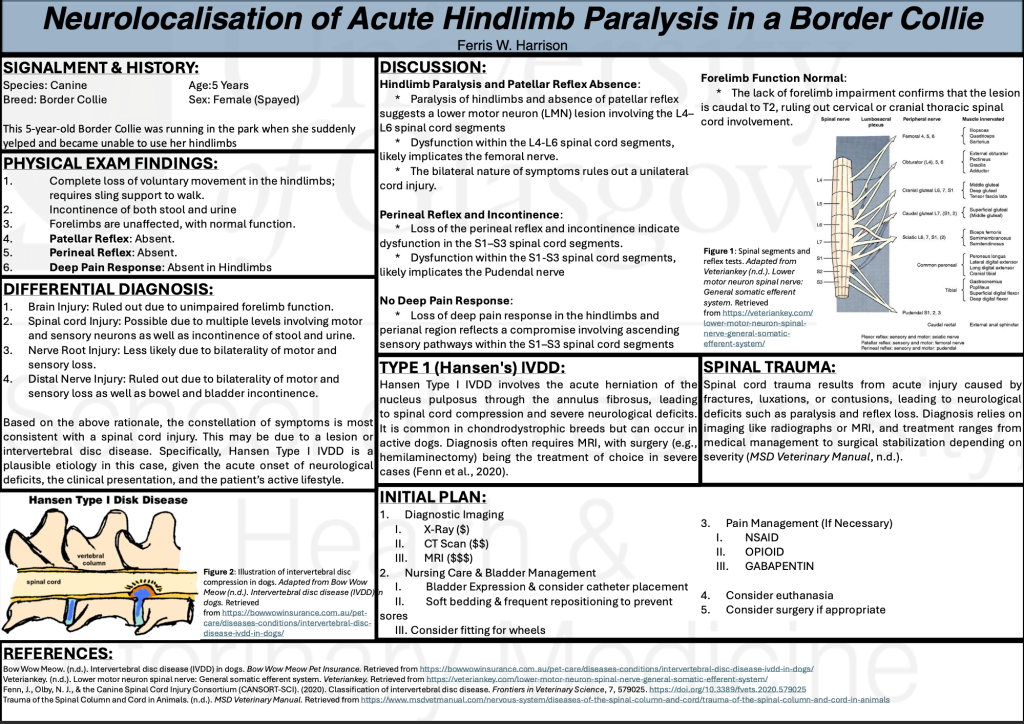

This poster presents my analysis of a case involving a five-year-old Border Collie with acute hindlimb paralysis. It includes a comprehensive assessment of clinical findings, differential diagnoses, and a proposed treatment plan.

Instructor Feedback

Instructor Feedback

References

- Cauzinille, L. (2000). Fibrocartilaginous Embolism in Dogs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 30(1), 155–167.

The presentation is well-organized and complete (including all the relevant information).

There is a correct analysis of the possible localizations, however, this is incomplete as a final localization is not properly mentioned. Your properly discuss an affection at the level of L4-L6 and S1-S3 spinal cord segments, but is this your final localization? Is then a multifocal localization? This rationale analysis is lack, and in this case the localization was L4-S3 spinal cord segments. To know that you should have check the withdrawal reflexes (which were affected) and then you could explain all the finding with only one localization.

The rest of the information displayed on the poster is correct except for 2 points:

- Discussion about the loss of deep pain response: this is not a prove of the localization, it is just a prove of the severity of the lesion! This is very important to differentiate.

- The differential diagnosis should include another common spinal cord disease that present acutely: fibrocartilaginous embolism (AKA ischemic myelopathy). Moreover, I do not think you should include a trauma as a differential as there was not a history of a traumatic event. Running in the park is not a trauma, and the description displayed for this case is the typical presentation for fibrocartilaginous embolism (= dog performing exercise and suddenly yelps and present neurological deficits).

Moreover, it should be discussed if X-rays is an option to evaluate a spinal cord lesion (mainly if there is not a history of trauma). In this case, none of the most likely diseases (IVDE and FCE) will be seen on X-rays, which means that owners will pay for a test that is useless. X-rays could be a good option in case of a trauma or if neoplasia is suspected (chronic history).

A very interesting point of discussion is to include euthanasia as an option BEFORE than surgery. Although the prognosis is worse in dogs with deep pain negative (compared to deep pain positive patients), it does NOT mean that there is nothing to do. Around 50% of dogs with a IVDE with negative deep pain will recover ambulation when performing a surgery. However, this surgery should be performed very promptly, and the vet should be aware about that in order to refer the case as soon as possible and give ALWAYS the option to the owner to decide. In case of a FCE, dogs can also improve without surgery but with physiotherapy. Therefore, I do not think euthanasia should be mentioned before surgery.